THE GREAT

TAMASHA COOKBOOK AND FAMILY

HISTORY

16

Further

Resolutions

Introductory

Note by Katy Widdop

This chapter is based on Ponsonby’s letters

home to Lord Sleyven (1829-1830), discovered in the library at Maunsleigh by

Jack Cooper. We also had access to Lord Sleyven’s own letters in reply. Our

grateful thanks go to the Maunsleigh Trust and the Librarian, Dr. Pierce

Dowling, for permission to access the Maunsleigh papers. In some places we have

given a reconstruction, combining information from several letters. At other

times sections of the letters are quoted verbatim.* We also found some very

helpful information in the Thomas family papers forwarded by Jane and Bill

Cooper, and we would like to express our sincere appreciation to Miss Thomas.

* Jack Cooper and Charles Babbage deciphered and transcribed

the

handwriting. Many thanks.

Extract from

an undated letter from Ponsonby sahib

to Lord Sleyven,

written shortly

after returning to Calcutta

The Darjeeling season drawing to a close, and the

knowledgeable already claiming that the rainclouds were gathering over the high

Himalaya, it was time to head back to Calcutta. No-one protested. In Tess’s

case, doubtless because John Widdop had decided to take some extended leave in

the city! There was also the reflection that if we had not set off home we

should quite likely have been caught up in a flood, or risked being trapped by vast

mudslides—in fact Tiddy reminded me of the time the regiment was stranded for

months in the foothills. I must say, I had completely forgot the incident—I was

not with you at that point, you may remember. It was the time I went on the

absurd bahloo hunt, amongst certain

other expeditions.

You may

recall that when the two older girls and I joined Tiddy in Darjeeling, Josie

went on down to Patapore with the Meggses. Yes, a baronet’s son was in the offing. We had originally

intentioned to head for Calcutta by way of Patapore to spend a few days there,

and come back with Josie, the Meggses and their connections all together, but

the rains struck just as we reached the turnoff, and so we carried straight on,

rather than waste time on a detour which would result only in our having to

turn round immediately. We reached Ma Maison without incident and were greeted

by the usual salaaming, feet-touching, flower garlands and protestations of

undying devotion. Funnily enough the house had not even been burnt down in our

absence, either.

Two days

later Miss Josie joined us, very flown with the news that Mrs Meggs’ sister,

Mrs Colonel Jeffcott, was to stay for a while at the Governor-General’s

mansion, and she had been invited to join the party. Whether Colonel Jeffcott’s

nephew, Alan J., the heir to Sir Alfred Jeffcott, Bart., was a factor, no-one

found the strength to enquire—the more so as, Miss Lucas having mentioned his

name, Miss Josie tossed her golden curls, sniffed, and pronounced: “A white

mouse. He has no presence and is utterly devoid of charm.”

“I dare say

she will do as well at Government House as anywhere, in Calcutta, in the

rains,” decided Tiddy baba. “After

all, it has a roof.”

“And very

possibly she will succeed in dashing the hopes of all the débutantes of

Calcutta by capturing young Lord Freddy Dewhurst’s affections,” added Miss Tonie,

smiling. “After all, he has a title!”

There was

general laughter, though Tiddy might have been heard to mutter, Cassandra-like:

“Honorary only,” and the household at Ma Maison agreed that Josie might as well

go with Mrs Jeffcott. Mlle Dupont did voice to me in private the thought that

the visit might do her some good socially, but could scarce do her any

otherwise, in fact would pander to her vanity, if it could do her no real harm.

She did not have to voice the other thought, that if we withheld our permission

Miss Josie would be unbearable to live with for the foreseeable future: we were

both very much aware of it.

Life went on very peacefully at Ma Maison,

with frequent calls from Collector Widdop, and the promised visit of Tom Harper

from Lucas & Pointer’s Lucas Hills tea plantation. Ponsonby was very

pleased to see that Miss Tonie’s manner to the latter was unchanged, in spite

of his social awkwardness, and that Miss Lucas appeared genuinely happy in John

Widdop’s company.

By the time the rice was knee-high in the

paddies all up and down the river, Josie had returned to Ma Maison, very puffed

up in her own conceit, although as yet no baronet’s son, white mouse or not,

had proposed, and nor had young Lord Frederick. Fortunately the fact did not

seem to lower her spirits. Then the news came that Lord Welling was expected in

India! This caused huge excitement, though as the correspondent was Miss

Partridge, the facts of the case were not absolutely clear. *

* The bulk of

the Partridge brother and sister’s papers went to Maunsleigh, but a few odds

and ends, including letters and some recipes in Miss Partridge’s own hand, made

their way into the Thomas papers, possibly via

Antoinette. We were thrilled to find this letter amongst them. The last page is

very stained and largely illegible but it did not seem to be pertinent,

luckily. –K.W.

Letter from Myrtle Partridge to Tess Lucas,

dated “Sept. 1829”

My very dear Miss Lucas,

How thrilled

dear Brother and I were to receive all your India news. Brother has asked me to

convey his very kindest regards to all of you, with wishes for your continued

health and happiness. As usual we spent some of the summer months at Maunsleigh

with our dearest Cousin Jarvis and “Midge”, as dear Lady Sleyven kindly insists

we call her, so Brother took the opportunity to show me in the big atlas in the

Library where Darjeeling is. What a very long way from Calcutta it is, to be

sure. I do trust that the journey will not prove too much for dear Tiddy—though

of course, as she has assured me innumerable times, she is an “old India hand!” The visit entirely

delightful, lasting a full two months, and would have been even more prolonged

at our gracious hostess’s urging, but that Brother and I were determined not to

outstay our welcome, as the saying

goes, and so when the warm August days drew to an end, set off for home as

planned. Indeed, we are only just returned to our cosy nest.

The company

there, if I may phrase it so, most congenial,

some of Jarvis’s closest friends present, with almost daily visits from Midge’s

friends from the neighbourhood, not

all, as dearest Jarvis at one point claimed in his joking way, “gossip and

teacups!” As you know, his old India friend Col. Langford is settled in the

neighbourhood, his charming wife, who of course is Midge’s former

sister-in-law, very ready to offer the most agreeable of dinner parties at

their gracious home, Kendlewood Plce., which Brother assures me is a Jacobean house,

tho’ not to be compared with the grandeur of Maunsleigh.

But then, at

Maunsleigh one made is made so comfortable, indeed, cosy, that one could readily imagine oneself in one’s own home (if

one may dare to make the comparison!), everything being so easy and sans façon under dearest Midge’s régime.

Good

gracious me, there was a time when such mere

connexions on the distaff side as

I and Brother would not have been warmly received at M. Great House! Well do I

remember the time that his late cousin’s late mother (wife of the then Earl)

snubbed dearest Jarvis’s own mamma and daughter to their very faces, my poor

cousin utterly crushed and the

unfortunate girl, I do not scruple to say so to you, dearest Miss Lucas,

weeping unreservedly after it for a good hour by the mantel clock, the same

little gilt clock that dear Jarvis had all through his India campaigns and has

on his very bedside table at this instant! He was the merest lad at the time

and having no notion how he might console them, rushed round to my humble little set of rooms (for we were not at

Little Froissart in those days, you know) and begged for his Cousin Myrtle’s

aid! So we went upon a shopping expedition and purchased a charming enamelled

clock at Brother’s advice (for his taste, as you know, does not err), the which

he duly presented to his mamma and sister, for their little downstairs parlour

(for it was scarce a salon, in those days). The which was the most delightful

and unexpected surprise. So his mamma said immediate that he must have the old

clock for his very own, and so it was!

But I digress! We enjoyed tea parties galore, if one may use the expression,

and numerous expeditions in the barouche, with a most pleasant trip to hear

sung Evensong at the Cathedral, for it is not so long a drive as all that, and

Dean Golightly, the most cultivated and gentlemanly man, whose mamma was a close

connexion of the Narrowmines (Lord Blefford’s family), always gives the most interesting

of sermons, entirely suited to the occasion, and never too long, a trap into

which even the most conscientious vicar, alas, may fall!

His wife, of course, is Lady Judith, née Wynton, Jarvis’s very own cousin,

and that branch, I do assure you,

always makes one feel extremely welcome and at home! We drove over to take tea

with her quite several times, sometimes in the company of her little daughter-in-law,

Polly, who is Midge’s own niece. Mrs Golightly the prettiest and most unaffected

young woman one could hope to meet and the babies the most adorable tots, to

whom the young mother is evidently so devoted, the prettiest of pictures

imaginable. The younger Dr Golightly has built a little arch, or arbour, in

their pleasant vicarage garden, up which he is training some climbing plants,

and to see the young mother with her children embowered therein is, I am sure, a

sight worthy of the brush of a Titian or a Raphael! The Titian at Maunsleigh,

dear Brother maintains, very fine, the subject entirely classical, and alone

would merit a visit to the mansion.

Lady Judith

also offered a dinner to which we were bid, and surprising it was to find thereat

an old acquaintance, if one may claim

him as such, from our last charming summer together at Little Shrempton! I wager

you will never guess, my dear Miss Lucas, tho’ dear Miss Josie may, if I give

you the hint L.W.!!

Yes! It was

Lord Welling in person, and asked so affably after all the family from Tamasha,

with a laughing reference to the splendid Tamasha

fruit-cake! Than which I am sure I have never tasted better, tho’ of course

everything from the Maunsleigh kitchens must be very fine.

He was very

well and his dear Mamma likewise, tho’ sadly her elderly cousin by marriage on

her mamma’s side, Lady Reardon, the former the Honourable Miss Catherine

Stoeve-Parkins, had lately died. The most sought-after débutante of her Season,

tho’ I dare swear as many as a dozen dukes’ and earls’ daughters launched that

year! So naturally she was in mourning.

His Lordship

was so glad to hear your India news, for he himself intentions a voyage to

India in the very near future! The dear

Dean, in his funning way, then pointing out he had best make sure the ship was bound

for Calcutta, for India is not small! Lord Welling, affable as ever, merely

laughing and saying that he was very sure it was, and his party, indeed, would include

some persons newly appointed to the G[overnor-General’s staff.]

[Most of

the rest obscured]

[I re]main, my very dear Miss Lucas,

Ever your most devoted,

Myrtle Partridge.

P.S. Since you so kindly expressed your appreciation of

my dear Mamma’s receet for Pickled Pears when last we met, I venture to enclose

the same. I have appended dearest Aunt Fanny Hurst’s hint for using up the

vinegar from pickles, in the hope that you may also find it of use. Ah, well do

I remember the times we had at Hurst Lodge in Somerset, when the late Capt.

Hurst, R.N. (Rtd.) was still with us, and Aunt Fanny in her best muslin cap,

which would seem enormous to you dear young people these days, but of course

the height of fashion when ladies wore so much hair, or, indeed, wigs, tho’

hers was always so thick, nay, luxuriant. Dear Martha, George and Agatha

Thorne-Pickens (the Sussex branch; he, of course, is now Sir George, and a

distinguished Member of Parlt.) used always to be there in the summers, also.

But that was many years agone, and you may not care for it, but then, a little

something different in a cool salad (or “sallet” as dearest Aunt Fanny would

always write it, in the old way!) can scarce come amiss, in the heat of India.

The sweetened vinegar or that of sour pickles will do equally well.

A Way to Pickle Pears

Take 1 pint of vinegar & 3 pounds of sugar

to 6 pounds of pears. Boil pears until tender. Boil vinegar and sugar together

with 1/2 tablespoonful of cinnamon, 1/2 tablespoonful of whole allspice, &

1 tablespoonful of whole cloves for fifteen minutes, then put in the boiled

pears, and cook all together half an hour before sealing in yr. jars.

A Use for the Vinegar Off Pickles

When yr. pickles have been used from

yr. jars, do not throw away the vinegar. Use it in yr. salad dressing in place

of plain vinegar. You will find the flavour much improves a salad.

When Tess read the letter out to the family

Josie seemed at first very pleased by the news that Welling was due; but having

re-read the salient passage over to herself, pointed out crossly that it was not

clear when he might have left! Had this dinner at the deanery taken place at

the beginning of the Partridges’ stay at Maunsleigh, in which case it might

well be supposed that Welling’s ship was overdue—that was, if it had indeed

been leaving almost immediately, the which was by no means certain, since they

had but Miss Partridge’s word for it—and what, pray, did “in the very near

future” mean? Or had it, on the

contrary, taken place at the end of their visit? Which could mean that he had

not in fact left until well after the ship which had brought the letter, and

might not be with them for months! And did anyone know if more persons were in

fact expected out from England to join the Governor-General’s train? For she

was quite sure that no-one at Government House had breathed a word of any such

thing, during her stay there! And in fact there was a scheme afoot for the

whole party to take ship for Bombay for an official visit before very many more

months had passed! Which, if persons of any importance were expected, did not

seem a likely contingency, did it?

Tiddy replied to this: “Is Welling a person of any importance?” but no-one else managed to

dredge up very much of a reply. Certainly nothing that would sensibly or

credibly contradict Josie’s reasoning.

Finally Mlle Dupont offered, in a very weak

tone for her: “You will just have to possess your soul in patience, my dear.”

To which Miss Joséphine replied with a toss

of the golden ringlets: “Huh! I do not intend waiting around in the hopes that

Lord Welling may condescend to honour Calcutta with his presence, I do assure

you!”

The family waited in trepidation, but to

their surprise Tiddy did not point out that in the circumstances she could not

do otherwise.

Extract from a

letter from Ponsonby sahib to Lord

Sleyven,

written from

“Calcutta, Jan. 1830”

...The

courtships continue apace, Tom Harper having returned to the hills but an

amazing volume of correspondence (permission having duly been sought and

granted) passing between the parties, and John Widdop having returned to his

District but ditto. The latter has already sought my permission to pay his

addresses to Tess: as an older fellow, he felt he did not have the right to pay

court unless he knew he had her family’s approval. It’s true he is nearly

twenty years her elder, but I told him to his face we could not hope for a

better man for her. The modest Tom Harper has not yet ventured to approach me,

but I am quite sure, if I may so put it, that Tonie is giving him sufficient

reason to be sanguine. Indeed, it is clear that I can cease worrying entirely

about the fates of the two elder Miss Lucases. Two more thoroughly decent

fellows than John Widdop and Tom Harper it would be hard to find upon the face

of the earth.

So clear,

indeed, is it that I shall soon be rid of the responsibility for Tess and

Tonie, that Tiddy marched into the study and cornered me behind Henry’s big

desk with the grim remark: “Tess and Tonie are going to take Collector Widdop

and Mr Harper, are they not?”

I murmured

agreement, asking whether she did not approve? She snapped back that of course

she did, to which I returned merely a mild “Good.” Then there was a slight

pause. Finally she muttered that the Collector mentioned that he is thinking of

retiring after another couple of years. I allowed that he has told me the same

thing, adding: “Perhaps your idea of his and Tess taking a house near to

Tamasha might be the go, then?”

“What? Yes,

not that,” she said, frowning. “The English climate will be better for the

children.”

“Why, yes,

I think so, Tiddy,” said I kindly, somewhat surprised, though the point had, I

think, been mentioned before, that it should have been so close to the

forefront of her mind.

Silence

again. I could not divine what was on her mind, so changed the subject and

asked whether she would like to help me with the accounts. She was taken aback

but said that she would if I trusted her to do so; adding the rider, not

unexpected, that it was very boring being a young lady at home.

“I know,”

said I, “and you were always quite good as sums, as I recall.”

She eyed me

uncertainly and pointed out that it was easier with an abacus. I preserved my

countenance and returned: “I am afraid that Calcutta would be shocked to its

marrow an I let you squat on the carpet with an abacus, Tiddy baba. But by all means use the little

desk, if you would care to. By the way, what did happen to Mr Krishnamurtee,

who used to help your father?”

I was not

sure she would know, but she explained promptly that he had to go back to his

village, his older brother having died and his old father being very frail. Henry

had offered to increase his salary so that he could send more money home, but

that was not the problem: it was that there was no-one to run the farm. –As you

will realise, this “farm” would be no more than a pocket handkerchief of land.

One water-buffalo, enough rice to feed the family in a good year, and an

apology for a vegetable patch. Plus the inevitable mango tree, no doubt. I just

nodded, and waited.

Tiddy

drifted irresolutely over to the second desk. “We could see if there is someone

the office could recommend to help you, Ponsonby sahib. I mean, as well as me.”

I agreed

that this was a good idea, but as she then, instead of sitting down to it,

fiddled irresolutely with the papers on the desk, I sighed and ordered her to say it. She turned and gave me a glare. “Very

well, then. You had best marry me, Ponsonby sahib.”

I had not

expected quite this, true, but since I had suspected it must be something

drastic, I was able to reply calmly enough: “Why, Tiddy baba?”

The glare

increased. “Because Tess and Tonie are going to take the Collector and Mr

Harper, of course!”

Quite. And

Josie would never for an instant contemplate allying herself with one who could

think of wearing a coat from the fell hand of Mookerjee. I said as much,

adding: “So do I have to marry you because you wish to get your hands on your

full share of Henry’s fortune—there is the consideration that on marriage it

will come into my hands and I may become entirely curmudgeonly over it—or

because you wish Tess and Tonie to have their full shares as proper

dowries—can’t imagine any fellows less likely than John Widdop and Tom Harper

to give a damn about dowries—or because—”

At this

point she shouted: “NO! Stop it!”

I’m afraid

I continued: “Or because you’ve decided that Josie, never mind the curls and

the big blue eyes and the social cachet

of having stayed at Government House, will never catch a title unless her full

share of the fortune goes along with the rest of it?”

“N—um, that

last is probably true,” she admitted, fair-minded and logical as ever. “But

that isn’t it!”

I noted that

it is a consideration with me, at which she brightened, but I quickly

continued: “No, a consideration which inclines me to do t’other thing, Tiddy. A

decent man will not be swayed, one way or t’other, by the lady’s fortune. I

don’t want to see Josie tied up to a worthless idiot who only took her because

the fortune went along with the rest of it, my dear.”

Tiddy bit her

lip. After a moment she said in a small voice: “But Ponsonby sahib, she isn’t very bright and—and she

is very vain, and—well, silly, really. Do you think that that sort of decent

man would really want her?”

I told her

that we should at least wait and see, advising her to bear in mind that a

fellow may appear young and callow but still have some good in him, and that with

the responsibilities of a home and children, even Josie may gain some sense.

I expected

a flash of temper, but no: she nodded thoughtfully and then pointed out that

Josie is very fond of small children. As Josie’s chatter about the Patapore

visit has included, in amongst the great flood of information about Mrs Col.

Jeffcott and her irreproachable connections, quite a lot about the Durrant

children from the next-door bungalow, I was not as surprised by this

information as I once would have been. I smiled and allowed that I had gathered

that, adding, in what I hope was not too pontificating a tone: “I think it is a

very hopeful sign. I have seen many pretty girls, almost as pretty as Josie herself, settle down to happy

domesticity. It is a natural progression, indeed: an early period of

considerable silliness au fond is

nothing more nor less than a search for a suitable helpmeet and provider—not of

a title or a fortune, Tiddy baba,”

said I with a laugh as she frowned and opened her mouth, “but of a domestic

hearth and babies!”

She went

rather pink and said: “Oh.” I could see she was thinking about it, so I just

waited. “Oh, goodness, yes, you’re so right!” she cried. “Look at Catherine

Doolittle and Martha Carruthers! I mean Catherine Dean and Martha Hilton, now.”

“Aye. The

silliness and the curls are Nature’s way of catching ’em that suitable provider

and ensuring the babies ensue!” I agreed gaily.

She nodded

hard. “Yes. That’s good.”

“So why this

haste to marry me?” I murmured.

She went

very red, and cried that it was not haste! “No?” said I, and waited. For a moment it almost looked as if

she would give in and tell me the truth... No. She merely said grimly that it

would be sensible: it would sort everything out, and it would be fair. Presumably this meant fair in that

the other girls would get their fortunes? I replied that none of them are in

want, and that I would prefer to wait a while to see if a decent man does turn

up for Josie.

“Very

well,” she said grimly, sitting down at the little desk and picking up a pen.

“What do you want me to do?”

Refraining

from saying: “Tell me the whole truth, Tiddy,” I set her to checking some

household accounts.

The weather had begun to warm and along

with the sprig muslins and the new straw hats there was already talk of whether

it would be Darjeeling or Patapore this year. Oddly enough there were few votes

at Ma Maison for Darjeeling and it was decided that the salubrious airs of the

tea plantation would prove so much more beneficial this year. Only Josie

dissenting.

“It will be vairy boring for her, Monsieur le Colonel,” admitted Mlle

Dupont. “And she has had this vairy flattering invitation from Mrs Jeffcott.”

The very flattering invitation consisted of

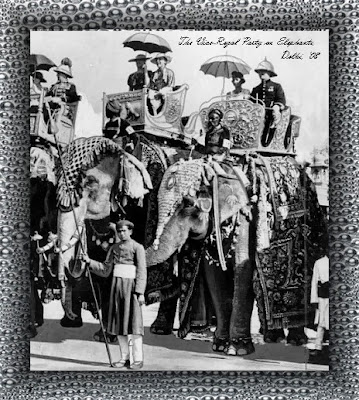

taking ship with Mrs Jeffcott and getting all the way round to Bombay in order

to assist the Governor-General in something-or-another. A parade through the

city, very probably—on an elephant, doubtless.

Ponsonby sahib found himself forced to enlighten Mlle Dupont’s ignorance—not

to say, to play the rôle of stern guardian. “I fear I must forbid it,

Mademoiselle: it would mean letting Josie out of our sight for well over six

months, all told; in fact, if the G.-G. means to go on to Delhi, as is rumoured,

at least a year.”

“Oh,” she said lamely. “I had no idea...

The distances are so vairy great here. Well, it seems sure that Lord Welling is

coming out: Mrs Doolittle had it from someone at Government House.”

“Good. Let her be content with that.

Besides, he ranks higher than little Alan Jeffcott’s pa, don’t he?”

Mlle Dupont smiled weakly and did not make

the point that Freddy Dewhurst’s pa, never mind if Lord Freddy were not in the

immediate running for the title, ranked considerably higher than either of them.

His young Lordship was predictably at Josie’s feet and she, almost as

predictably, was alternately spurning and encouraging him.

Charlie Hatton, who was brazenly showing

his nose around the town again, was offering him a challenge, but as Josie

collapsed in giggles every time she laid eyes on him it could not have been

considered a serious one, and in fact over the cigars and chota pegs the odds were fifty to one against him. Lord Alfred

Lacey, however, might have been considered a much more serious contender, were

it not that Josie had condemned him in the family’s hearing as “old” and

“pudding-faced” and, possibly the coup de

grâce, “always pulling at one’s waist in the waltz.”

Unfortunately neither Mademoiselle nor

Ponsonby sahib thought the thing

through sufficiently to realise that it was Lombard Street to a China orange

that both Lacey and Lord Freddy would be off with the Governor-General’s party

to Bombay very soon.

Josie, however, made the point immediately she

was told she might not go, duly following it up with floods of hysterical tears,

accusations of meanness and favouritism on the part of her guardian, wishing to

be dead, and further accusations of never being allowed to enjoy herself—and

etcetera.

Poor Mlle Dupont bore the brunt of it: both

Tess and Tonie were completely preoccupied with their own thoughts and happy

plans, and Tiddy basely escaped to the study on the excuse of helping Ponsonby sahib with the accounts. Or simply

escaped—there were days when Mademoiselle did not lay eyes on her from dawn

until nearly dusk. True, coping with Josie was no sinecure, so it was quite

some time before the maiden lady realized in dismay that on these occasions of

Tiddy’s absence, she was not simply buried in the accounts with her abacus, and

eating her midday meal at the desk like a native clerk or squatting in the

kitchen with the servants.

“But where is she, monsieur?” she cried.

Ponsonby sahib passed his hand over his forehead. “Er—thought she was with

you and the other girls, Mlle Dupont.”

“Mais non, mais non!

Tess and Tonie are working quietly at their stitchery in the little

sitting-room and Josie and I have been for a stroll.”

“At least you’ve managed to get her out of

the house,” he said heavily. “Er—have you tried the kitchen, Mademoiselle?”

Mademoiselle glanced at the study clock. “Eugh—non. At this hour? No.”

Resignedly he rang the bell. Ranjit Singh appeared

in person, salaaming. Not a good sign, on the whole.

“Ranjit, where is Tiddy baba?” he demanded baldly.

Ranjit bowed very low. “Tiddy baba was sitting on side verandah,

Colonel sahib.”

|

| "A corner of the side verandah, Ma Maison" Sketch, pen & ink, artist unknown, circa 1930. From the Widdop family papers |

Ponsonby did not fail to register the tense

used. “Indeed? Then pray have her fetched, ekdum.”

“Very good, sahib: ekdum!” Bowing yet

again, the major-domo exited.

They waited, Ponsonby with his mouth very

tight and Mademoiselle looking at him doubtfully.

Ram appeared, bowing until his nose touched

his knee. “Pardons, great zemindar, huzzoor. Tiddy baba is not on side verandah.”

“Ram, where is she? Did you see her go

out?” demanded Ponsonby sharply in the language of the man’s home village.

Falling

to his knees, Ram declared that had he seen Tiddy baba with his own eyes leaving the house unescorted he would have

stopped her an it were at his very life’s expense, and that the defender of the poor was his father

and his mother.

Grimly Ponsonby translated this for Mlle

Dupont. Adding to her face of dawning consternation: “Reading not very far

between the lines, he knows d— well that she has gone out. Though I dare say he

did not actually see her—or rather, he may well have seen her, but she was not

unescorted.”

“That Black woman,” said Mademoiselle

between her teeth.

“Mm. Nandinee Ayah.” –Here Ram jumped sharply, and endeavoured to cover the

movement by touching his forehead to the study carpet.

“Get

up and get out,” said Ponsonby brutally in his native tongue.

“Monsieur,

you must sack the man!” cried Mlle Dupont loudly as the bearer shot out.

He passed his hand across his forehead once

more. “Chère Mlle Dupont, you have

not seized the essence of the Indian servant. They all know—Ranjit as well.

That is why he sent Ram with the message. Doubtless his statement that Tiddy

was sitting on the side verandah was perfectly true. That would have been

before she went out.”

Mademoiselle lapsed into French, with much

waving of the hands.

“Oui, j suis d’accord avec vous,” agreed Ponsonby heavily when she had at last run

down. “Mais il n’ya rien à faire, sauf

attendre qu’elle revienne à la maison. Donner leur congé aux domestiques ne

servirait à rien. Le domestique indien est ainsi: il faut s’y rendre compte

et—eugh—apprendre à supporter la chose—quoiqu’insupportble qu’elle soit.”

“Bên—s’y résigner, en effet!” she cried indignantly.

“C’est

ça. Ça, c’est bien l’essentiel de l’Inde,” he murmured.

After a moment Mademoiselle said grimly: “I

see. I begin to understand the implications of the expression ‘old India hand’.

I do not think that I shall use it lightly, in the future.”

Ponsonby sahib just smiled, very slightly.

Tiddy and Nandinee Ayah returned when the shadows were long and blue across the

immaculate lawns of Tamasha and mali

was pottering around watering the ginger plants. By this time Ranjit and two

bearers were stationed in the front hall, and Ponsonby and Mlle Dupont in person

were on the side verandah. The culprits, however, made no attempt at

concealment, but walked straight under the swag of vines over the archway and

up to the verandah.

“Where have you been?” demanded Tiddy’s

guardian without preamble.

Immediately Nandinee Ayah fell to her knees and, saree

pulled well over her face, began wailing that there was no harm in it, a simple

visit to a friend, and they had taken a tonga

there and another back and the huzzoor

was her father and her mother—

“Chup!

Bus—BUS!” he shouted.

The ayah

subsided and he said: “Well?”

“We went to see Mrs Mookerjee,” said Tiddy calmly.

“You know, she’s Sushila Ayah’s

sister.”

“Oh? Then why did Sushila not go with you?”

“She did. She’s staying the night. They’ve

arranged a match for Ravi—I don’t think you’ll remember him, Ponsonby sahib. He’s fifteen, now. The girl is from

a very suitable family, with an excellent dowry.”

“I see. They’re having a party, then.”

Tiddy gave the affirmative head-wobble. “Yes.

–Nandinee Ayah! The pistah barfee!”

Giggling, the ayah got up and, bowing profoundly, produced a package from the

recesses of her garment.

“Barfees,” said Tiddy helpfully. “Special

ones, all of pistah—I’ve forgotten

the English word again, Ponsonby sahib.”

“Uh—so have I. Des pistaches,” he said limply to Mademoiselle. “Small green

nuts.”

Helpfully Tiddy opened the package and held

it out.

Mademoiselle recoiled. “These are not nuts!”

Bursting

into excited speech, Nandinee thrust the package into Ponsonby’s hands.

He took a deep breath. “Never mind Mrs Mookerjee’s

sweetmeats, Tiddy. You are not to go

wandering off into the town without telling either Mademoiselle or me!”

“I’m sorry. We left early because we wanted

to get to the market first. You were both asleep.”

“So if you leave so early, when are you on

the side verandah?” cried Mademoiselle loudly.

Tiddy blinked. “This morning? For chota huzzree, of course. I mean, we had

a petit déjeuner, Mademoiselle,”

Ponsonby

sahib coughed suddenly. It was more

or less a literal translation.

Tiddy’s eyes twinkled but she said

demurely: “I’m very sorry if you were both alarmed, but of course I had the ayahs with me.”

“Nevertheless you knew d— well it was wrong

of you. Get inside,” said Ponsonby tiredly. “I suppose there is no point in sending

you to bed dinnerless, if you’ve been stuffing yourself all day?”

“Well, no.”

“No.

You may go to your bed ekdum,

however.”

“Very well.” Bidding them both a sweet good-night,

she went into the house.

After a moment Ponsonby said limply: “She was

quite safe, Mlle Dupont. I suppose we should not refine too much upon it. Er—and

there is no danger she would have been seen by any of the sakht burra mems of Calcutta society.”

“No, because

she was in the native quarter!” snapped the little Frenchwoman.

“Yes. Well, we shall just have to try to keep

a stricter eye upon her,” he said mildly.

Oh, dear: Mademoiselle took this unto herself

and said very stiffly indeed: “Naturellement

I was at fault, I do not deny it, monsieur.

Pray forgive me. I shall be vairy much on my guard in the future.” With this

she gave a horribly formal curtsey and exited in good order.

Ponsonby sahib sat down suddenly upon the floor of the verandah. “What a storm

in a teacup,” he muttered. After a little he realised he was still clutching

the package of barfees. He shrugged a

little and took one. “Why not?” he

murmured, and ate it.

Pistachio Barfees (Pistah

Barfee)

Make a syrup from 1/2 lb. of sugar and 1

cup of water. The syrup is ready when a drop forms a ball when put on the edge

of a cold dish. Pound well 2 ounces of pistah

[pistachio nuts, shelled & peeled]. Stir them into the syrup. Continue to stir

until the mixture is dry & begins to form a lump. Turn onto a greased platter.

This may pleasingly be decorated with silver cashoos. Cut into small diamonds

or triangles when cool. These sweetmeats will keep well.

The barfees seemed to clinch it—they were certainly

homemade, and excellent, just the sort of thing that did get prepared for

celebrations. Ponsonby sahib did not,

therefore, check to see just what part of the day Tiddy might have spent at Mrs

Mookerjee’s. A mistake on his part, as he was later ruefully to admit.

After this episode Tiddy took care always

to be down for breakfast when Mlle Dupont was. After checking up on her for some

time, Mademoiselle gradually relaxed her guard, as she did always seem to be

working away in the study when she was supposed to be. It did not occur to the

little Frenchwoman—she was, of course, one of those people who are completely

sure of themselves and of the rightness of their way of thinking—that in India

the vast majority of people rose with the sun, or even before it, and that a

large part of the day’s activities took part before the feringhees deemed it a suitable hour to break their fast. Nor that

Tiddy, having been raised by Indian servants, might feel herself one with this

vast majority,

The thought did occur to Ponsonby, but as

he knew she was sensible enough not to go out without an ayah—and that the ayahs would

certainly not let her do so—and at heart shared her opinion that a young lady’s

conventional fate in Anglo-India was a very boring one, he did not bother to

police any early-morning comings and goings that might have taken place. It

would not be until quite some time later that he would admit to himself—and,

indeed, to his friend Jarvis—that he was not examining the thing too closely, as

he did not wish to alienate Tiddy and have to forgo her company in the study.

Extract from a letter from

Ponsonby sahib to Lord

Sleyven,

written from Calcutta in 1830

The summer

season is not yet upon us—though feverish plans are being made for it all over Calcutta,

or so one gathers—and Tiddy and I are still struggling with mounds of accounts,

though Lucas & Pointer’s Calcutta office has produced a solemn Mr Ferdinand

Maltravers to help us. No, you have it wrong, black as your hat, the full name

being Ferdinand Gupta Maltravers. The great news is that Miss Josie has received

yet another flattering invitation.

“Who is

this Mrs Gordon Dalziel?” I groaned.

Mlle Dupont

reported that it was, she was

reliably informed, the Duke of Lochailsh’s family, though only a very distant

cousin, but the lady was a close friend of Mrs Colonel Jeffcott and I had met

her.—No, I had not.—Yes, the lady with the dark curls and the feathers held

with a diamond clip—that cut out a dozen of ’em—at Mrs Colonel Voight’s select

card party the previous week.—Er... Oh, the pleasant, plump woman with the

merry-faced little daughter with the tiny dark ringl—No. Younger: her youngest

child was but four years of age and I must have heard Josie speak of him.—Oh,

up at Patapore? Thought that was some other name—Not them.

I gave in

and said that I did not recall her but we had best pay a call and see if she

was likely to provide suitable chaperonage—or any chaperonage—if Josie stayed

with her for a week or two. Though if the intent was to make it more than a

week or two, indiscernibly merging into a stay up at Darjeeling with

her—Mademoiselle was sure it was not.

We went,

the woman seemed pleasant enough, the husband seemed very pleasant and

sensible, and if they were a little under my own age, still at least they were

not young and silly. Two of the little ones were allowed to come in and meet

the visitors and Josie did seem genuinely taken with them; and Mrs Dalziel did

seem a genuinely fond mamma; so with these promising auguries to encourage me I

gave my permission. Instantly metamorphosing into the kindest guardian ever.

Without even a demand for more pin-money.

|

| 'The Dalziel children, Calcutta" Watercolour, circa 1830, artist unknown (attributed to Antonia Lucas) (Formerly in the collection of the Duke of Lochailsh) Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

“Doesn’t

she want more pin-money?” I croaked as she danced out to review her entire

wardrobe. Instantly Tiddy baba explained

that one cannot spend one’s pin-money when one is face-down upon one’s bed

sobbing one’s heart out and refusing dinner. Or alternately sitting up

cross-legged upon one’s bed eating bowlsful of jullerbees and rasgullahs.

In answer to which I could only recommend weakly that she tell her she’d get

fat.

Ctd., later.

So Josie is

with the obligeing Dalziels, who as far as we can ascertain are taking her to

exactly the same picknicks, parties and dances she would have attended had she

stayed at home—though admittedly Calcutta would not then have been favoured

with the sight of the inarticulate Lord Freddy Dewhurst attempting to escort

Miss Josie, an extremely fat old ayah,

and two Dalziel little ones for a morning walk!

Now, this

really is an exciting piece of news, Jarvis. Tom Harper appeared unannounced in

Calcutta. He immediately requested an interview with me, in which he behaved

like the firm-minded, principled fellow he is, admitting that he is nothing

much and can offer Miss Tonie only a very simple life, but—very firm—she seemed

very happy during her stay in the hills and he thinks he can give her the sort

of life which would suit her. And that, should I give my permission, he would

insist that any monies which were due to her from her father’s estate should be

tied up for their children.

Naturally I gave him my permission to speak

to Tonie, adding that I was sure he could expect a favourable reply. I then

remarked that his decision about the fortune was very sensible indeed, but a

trifle precipitate, adding that one never knows, in life, when a largeish sum

might be needed, but that I agreed that it would be quite appropriate to tie up

the greater portion of the inheritance. I then explained very clearly exactly

how much the inheritance stands at, at the moment, and how very much larger it

would be should I fulfil the conditions of Henry’s will.

Had I not had a pretty fair estimate of his

character already his reactions would have been most enlightening. He was

surprised and somewhat shocked at the amount of current sum due to Tonie,

admitting that he had thought it half that much and adding that the most of it

would most certainly be put in trust for her children. Then when I revealed the

full amount he was horrified and sat there with his mouth agape for some time,

his big hands clenched on his sturdy knees. Then he went very red and

stuttered: “Sir—I can’t—I had no idea!” At which I got up, patted him on the

shoulder and said: “Of course you had not, Tom. I doubt it will ever come to

her, you know, for Miss Lucas is also about to contract a very suitable

engagement and the other two are by far too young for me to consider.” After a

moment he managed to utter: “Thank you, sir. But—but if it will come to our

children—it’s too much!” As you know, I am of the opinion that the whole thing

is too d— much for any five human beings’ needs, but I said merely: “Rubbish.

She is waiting for you in the small salon. Ram will show you the way. Do not

keep her waiting any longer, it would be too cruel. Ram! Koi-hai! Ram!” At which he stuttered out thanks and allowed himself

to be shown out by the beaming, not quite

congratulatory Ram.

I sat back

down in my chair reflecting that that whole conversation would have been a most

salutary lesson for both younger Lucas girls in how a decent man behaves with

respect to a girl’s fortune and that it was a great pity that Josie could not

have been present to hear it. Not Tiddy, no: I was d— sure she was squatting

out on the verandah just by the windows. After a few moments I made up my mind

to it, opened the French doors, and said grimly to the bundles in the sarees: “See?”

Nandinee Ayah gave a squawk, pulled the saree even further over her face, and

scrambled off, but Tiddy baba got up,

looking defiant, and said: “See what? I have always known he was a decent man.”

“Good,”

said I, still grim—the effort of trying not to laugh, you understand. “I only

hope you can give Josie a full report in terms she will understand.”

“She never

listens to me,” she said lamely.

“Nevertheless I should be grateful if you would try. Now, go on: jao!”

She bowed

and uttered obediently: “Ekdum,

Ponsonby sahib,” but it was but a

lame effort, and she scuttled off even faster than the ayah!

Well, it is excellent news, and we are all

very, very pleased about it. Even Josie’s heart appears to be in the right

place after all, for she congratulated her sister most sincerely, in fact

hugging her very tight and asking anxiously, with not an arrière-pensée in sight: “You will invite me when you’re living at

Lucas Hills, will you not, you, Tonie? Oh, wonderful!”—as the answer was of

course in the affirmative. “And I dare say that before so very long I shall be

an aunt!”

Extract from a second letter from

Ponsonby sahib

to Lord Sleyven, written from Calcutta in 1830

No sooner

had our household accustomed itself to the huge excitement of Missy Tonie’s

engagement—though it would not be true to say, settled down after it—than lo!

John Widdop turned up! He hoped I would not think it too soon but it was

getting on for a year, since they had met, and he was not getting any younger—

I laughed, but admitted I had something to tell him before I allowed him to

make the offer in form with my utmost good will. He was mildly surprised but

sat down and listened quietly. I told him as much as I had Tom Harper, and no

more. He is, of course, a much more sophisticated man, and so had had some idea

of how warm Henry Lucas had cut up.

“I see,” he

said quietly. “I did not know Lucas very well but I should have thought he had

more sense than to leave you in such an anomalous position, Gil.”

“Mm, me,

too,” I admitted wryly, and just waited.

“Well, in

the unlikely event that you decide to tie yourself up to either of the younger

girls, I shall be prepared,” he said lightly, “to build Tess at the least a

Blenheim, if not a positive Castle Howard.”

“In the

event you do,” I returned drily, “I promise to come and visit at it wearing a

bejewelled pin in me turban like a nawab.”

He smiled.

“I shall discuss it with her, of course, but I’m quite sure that whatever the

sum is, she’ll be happy for us to tie up all but a couple of thousand in the

children. If I wanted a wife who desired to cut a dash I should not be offering

for Tess.”

“Then you

had best go and offer ekdum,” I

replied, and he wrung my hand hard and hurried off to her.

So it was settled, for it seemed foolish to

wait, all parties being so evidently well suited, that towards the end of the

hill season Tonie would marry Tom Harper and Tess would marry John Widdop in a

quiet joint ceremony in the hills. It was a tiny community, of course, but

there was a little church—attended mainly by Tom himself and the Meggses, as to

the Lucas Hills plantation, and by the manager, his wife and family from Mr Timothy

Urqhart’s neighbouring tea plantation, plus a handful of chee-chee clerks and

their wives from the plantations and what few natives the earnest Reverend

Joshua Sprigg and Sprigg memsahib had

managed to convert to a sort of Christianity. Offerings of garlands, rice and ghee not being what was customarily

expected of an Anglican congregation.

Final extract from a second letter from Ponsonby sahib

to Lord Sleyven, written from Calcutta in 1830

And so the puzzle of what was to become of

the two older Lucas girls is resolved, after all, and they are to live happily

ever after, as far is that be possible within the laws of the universe as we

know it. And, as I said to Tiddy baba,

it can surely do no harm to make an offering to any god that the ayahs wish. To which she returned

dubiously: “But Ponsonby sahib, to

Ganesh? He is the

patron god of business!” I reminded her, as sedately as I might, that the

elephant-headed god is also the remover of obstacles. This caused great relief

and she went off happily to the temple with the offerings of garlands, rice and ghee.

–Does she believe? An interesting

question. What is belief?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please add your comment! Or email the Tamasha Cookbook Team at infoteam@senet.com.au