THE GREAT

TAMASHA COOKBOOK AND FAMILY

HISTORY

8

Return to

India

An Indian Saying about Unglazed Clay Pots

(which are customarily broken

after use)

Like pots of clay, an untrue friend

Is quick to smash, and will not mend;

Like pots of gold the righteous friend,

Is quick to mend, and will not bend.

From the

unfinished MS., circa 1899: Our India

Days

Chapter 9: Our Return to India

Another lovely day! Mayhap we are in for an

Indian summer, indeed! –Tell you

about India? You must surely have had enough of the maunderings of three old

ladies—Well, thank you, Matt, dear one! You are too kind! Well, no, there is

not very much in the letters about elephants or camels, Tessa, darling—nor, as

Matt says, water buffalos—for one would not write of them to someone who knew

the country. How far did you get, Matt? Oh, yes. The letters to Dr Little

ceased when we left for India. The rest are largely Ponsonby sahib’s letters to Colonel Wynton—Lord

Sleyven, as he was by then. Now, we shall have to think, children, for to us it

was like coming home. The sights were familiar to us, not strange and exotic as

they would be to you. Gil baba may

sit on his Grandmamma’s knee for the story—yes!

The Voyage Home

|

| "Clapping on Sail" Oil on canvas, circa 1860? Artist unknown Courtesy of Miss Thomas |

We took ship in a fine clipper of the Lucas

Line from Southampton and after a rough enough time of it in the Channel,

during which all of our party were horridly seasick but for Tonie and Tiddy baba—yes, even Ponsonby sahib, Matt—sailed eventually into

calmer waters, which enabled us to all to gain our sea legs, as they say! That means to get used to life on board a

ship which rocks and up and down, Tessa. We took water at Lisbon—no, the ship

was not racing out for tea, Matt, though her eventual cargo would be tea,

spices, and silks—as we were saying, we made port at Lisbon, and funny it was

to see one’s fellow passengers stepping off onto dry land and experiencing the

curious sensation of its going up and down! For when one is become used to the

motion of a ship at sea, somehow or another one’s inner self seems to believe

that that is the norm and stable land is the exception!

Lisbon is in a country called Portugal, Gil

baba, where everyone talks a

different language from English, and they have pretty white churches, so we

took a carriage and went to see a church with a priest, as they call their

vicars, in an embroidered robe, saying the service, and then had a nuncheon of

the oddest little fried fishes with very strong, hot coffee. Then it was back

aboard and ho! for the open sea: the great Atlantic off the coast of Africa.

The wind was with us and the captain clapped on sail. And a sight it is to see,

when the sailors scramble up the rigging to release the tops’ls! The canvas

shakes out with a rattle and a whoosh, and one feels the deck heel under one’s

feet as she picks up speed!

We made a stop in Cape Town, which is in

South Africa, where the native people are very black-complexioned, much darker

than the Indians, but did not see very much of the city, for we were whisked

off by a Mrs Samuels who was the wife of an English official, and made very

welcome at her home. No, just a big white house, Matt. Not as big as our dear

Tamasha, but certainly English in style. The meals she provided were English,

too, but with the addition of some of the tropical fruits which grow so well in

the those countries, like melons and mangoes. No, we do not have mangoes in

England, dear ones. Big yellow fruit, bigger than an apple, sometimes with a

red blush on the skin. Flatter than an apple—goodness, how hard it is to

describe something which is so familiar! The flesh is more like a ripe peach

than anything. No, a smooth skin, Matt, but one does not eat it. One cannot

describe a taste, Tessa, dearest! Sweet but—well, not wholly unlike peaches.

More—well, aromatic is not the word, but it will do. As Tonie says, many

tropical fruits have almost a putrid odour, but we do not wish to give you

children the wrong impression. There! Matt is crying “Ugh!”, but they do not

taste rotten, they are delicious!

Thank you, Tessa, darling, of course you

would pick a big juicy mango for your Grandmamma and great-aunties if we had a

tree! Orchards, Matt? Well, possibly one could, but every poor family has a

mango tree beside their little hut, in India! Just as all the villagers here

have a currant bush—why, yes, indeed, Matt: that logical mind of yours, again!

No, Antoinette, one does not stew them, but a tasty pickle is very often made

of the unripe ones. Very salty and sour, children, you would not care for it.

Antoinette, dearest, there is little point in telling you a receet for mango

pickle, for one cannot get the fruit here! Er... there is nothing really like

it, dear girl, but Tonie will write you out a receet for an apple chutney which

is something like a sweet mango chutney, though we never had it in India.

Great-Aunt Tonie’s Apple Chutney

Boil together 3 pounds of sliced apples, 2

pounds of sugar, & a quart of strong vinegar. When this begins to get like

jam, add half a pound of raisins, four teaspoonsful of finely-minced garlic,

two tablespoonsful of thinly-sliced green ginger, one teaspoonful of cayenne

pepper, & 1 oz. of mustard seed. Let simmer a while, then bottle and expose

to the sun.

The tropical fruits being a foretaste of

India, we took ship again eagerly, and rounded the Cape of Good Hope without

incident—though those seas can be very, very rough at times, and many ships

have come to grief, there—yes, Matt, but not in front of the little ones,

please. Tessa, ask Matt to show you on the globe: the Cape of Good Hope is

right at the bottom of the enormous land mass of Africa—and, indeed, in the

southern hemisphere: we had crossed the equator, with a certain amount of silly

dressing-up and some horseplay by the sailors. It is a time when a sensible

captain permits them some leeway: for a long voyage can be very dull for them,

if the weather holds.

We had fair winds and good seas across the

Indian Ocean, and the captain navigated us across that expanse of open water

most capably. –They use an instrument called a sextant, Matt, and take

sightings of the sun and the stars, and check them by the ship’s

chronometer—like a special clock, Gil baba,

a special clock which is never wrong. Not a grandfather clock like the

long-case clock in the front hall, no, dearest. Alas, that is all we can tell

you, Matt, for none of us has a scientific bent. –Would Ponsonby sahib know? He probably would, dear, for

the officers have to learn an amazing amount of mathematics and so forth—yes,

Matt, mathematics are definitely involved in becoming a ship’s captain, and the

officers of the Indian Army have to learn to navigate themselves and their men

across empty stretches of wild terrain, and then, if they are using the big

guns, there are calculations involved there, also, and that is more

mathematics, you see? Words like vectors and—and declinations, dear boy.

Matt, Ponsonby sahib would be happy to tell you, but pray do not run and ask him:

Dr Fortescue has said he must rest at this hour of the morning, remember? No,

Tessa, Ponsonby sahib is not sick,

but he is a very old gentleman. Yes, eighty-six: that is very old.

|

| "Gil Ponsonby in later life" Pencil, watercolour, circa 1850. Artist unknown. From the estate of Jarvis Wynton, Fifth Earl of Sleyven. Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

No, no person is as old as Father

Christmas, Gil, dear. Hush, Matt! Or you may not see Ponsonby sahib. You shall all have a glass of

milk and a slice of bread and butter at eleven, and by that time he will be

downstairs. No, Gil, it is not nearly eleven yet. Yes, we know you are also a

Gil, but Matt wishes to consult his grandfather on a serious subject, dear. So

you must just tell him “Good morning” and give him a big hug and kiss and then

let Matt talk. Of course, Tessa: you as well; Ponsonby sahib always loves to see you children!

Where were we? Approaching the coast of

India, of course! The ship put in briefly at Madras, where some passengers got

off, and we were welcomed most kindly by a gentleman who worked for John

Company—the East India Company, yes, Matt, Antoinette will make sure she writes

that—and dined with him and his pleasant wife that night. Not Indian food,

Matt, billayatee khana—er, an English

dinner, dear. Very formal, with many place settings and several courses, and a

great crowd of English persons there, dressed in their best. Gracious,

Antoinette, do not write “stuffed into their corsets”, whoever put that phrase

into your head? Oh—your Great-Aunt Tiddy. She is not wrong, dearest, we must

admit!

Yes, some of us were disappointed that it

was not Indian food—of course not Mlle Dupont, she was not accustomed to it at

all! We cannot recall precisely what was eaten, at this late date, but it was

very English and very formal. White soup? Yes, Great-Aunt Tonie is doubtless

correct in saying that there was white soup. Oh, dear! White soup, roast

beef—we feel sure there was roast beef, in our honour!—with French wines, and

the punkah-wallahs working the big

fans above us non-stop in the oppressive Madrassee heat! Are we English not

absurd? Er, never mind, dear ones. Suffice it to say we saw very little of the

town and had it not been for the dark faces under their stiffly starched,

winged turbans serving us at dinner, would scarcely have known ourselves in

India at all! And the fans, yes, Tessa, darling, exactly!

As to

how a fan could be up above us, Matt…

|

| "Collector, Wife & Officer at Dinner with a Punkah-Wallah" Gouache, circa 1810, artist unknown. Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

Your Great-Aunt Tonie will certainly sketch

you a ceiling fan, yes, though we cannot explain the precise mechanism which

allows the punkah-wallah to move it. ...There,

now! Exactly that! Yes, just a great flap of stuff, Tessa, not a pretty lady’s

fan with its folds, at all. There is a rod, as you see; the punkah-wallah works the long, long rope.

At Tamasha he would sit outside on the verandah and work it with his foot. Very

well, Tonie will draw you a punkah-wallah

as well! …There! Is she not clever? But you had best consult Ponsonby sahib about the rod and how it makes the

punkah flap backwards and forwards.

Home to Calcutta

|

| "Calcutta in the Early Days" Mezzotint, hand-coloured, circa 1798 (from a portfolio of mounted sketches & prints, Maunsleigh Library) Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

After the disappointment of Madras most of

us were looking forward eagerly to Calcutta and it was not long at all before

the ship had us there. Calcutta is on a river called the Hooglee, dear

ones—yes, a funny name, Gil!—and the water thereabouts is very shallow and so

the big ship moored out in the deeper water and we came ashore in lighters. And

soon we were on dry land with all the familiar smells and sights of our home

town surrounding us!

Porters? Porters galore, dressed in grimy

shirts and dhotees, trying to take

one’s bags out of one’s very hands, beggars in rags clamouring for baksheesh, and rows of tongas and tikka gharries lined up waiting for passengers with the poor, bony

horses endemic to the Indian way of life harnessed up, the ones driven by burly

Sikhs, big, bearded men in turbans, looking as if their large driver were more

than enough for them to pull without adding a load of feringhee passengers and their baggage! –No, not Pathans, Matt, one

sees very few of them in Calcutta, it is too far south. Sikhism is a type of

Indian religion, dear, which requires that the men never cut their hair or

their beards. –Not odd at all, Antoinette, for one never sees the hair, it is

always concealed within the turban and they have a particularly neat way of

winding the beard up also, often confining it tightly within a net. In fact

Sikhs have the neatest appearance of all the Indian peoples.

But the sights and the smells—the crowds of

dark-faced people, the little cow-dung cooking fires with their slightly acrid

but not unpleasant smoke—it is just grass, Matt, when one thinks about it—the

discarded mango stones and so forth rotting in the gutters—all these were the

least of it: we were also surrounded, nay inundated, by the sounds! You have

never heard anything so noisy as a great Indian city, dear children!

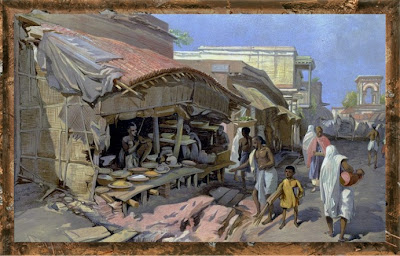

|

| "The Bazaar, Calcutta" Oil on canvas, circa 1815, artist unknown. From the estate of Jarvis Wynton, Fifth Earl of Sleyven. Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

There are street criers shouting their

wares, and every tonga seems to have

a particularly loud bell, with or without more bells on the harness of its bony

nag, and whether it do or don’t the driver will be shouting at the other drivers

to give way, and all the waggoners shouting likewise, and the clatter and

rumble of the carts and waggons, and the noise of this, that or t’other being

loaded or unloaded, with more shouting, and just when you think it cannot get

noisier a great, lumbering coach will appear with the man up beside the driver

blowing on a horn! And there are street musicians, hooting, twanging or

thumping away in the hope that one will toss them a few annas—like farthings, Gil baba,

not a name—and even the odd snake charmer or two blowing on their pipes! –Of

course, Matt: snake charming is quite popular in India, we have seen

innumerable snake charmers! The man squats in the dust blowing on his pipe and

the snake—a hooded cobra, dear ones, a very dangerous snake indeed—rises slowly

from the basket before him, swaying in time with the music, or possibly, as

Great-Aunt Tonie says, in time with the swaying of the pipe as the man rocks

slowly back and forth! –There, she has sketched you a snake charmer! A snake

would normally bite, yes, Tessa, and you would die of the bite, but it’s said

that these cunning snake charmers have the trick of removing the poisonous

fangs, rendering their snakes harmless. No, Gil, one would not shoot the

charmer’s snake, his snake is the poor man’s way of making a living, and how

would he feed his little brown babies if he could not make money?

The cries of the street vendors,

Antoinette? They are cacophonous, dear girl, so be warned! Very well, your

Great-Aunt Tiddy will demonstrate.

“Hindoo

panee! Panee! Hindoo panee!—Panee, panee! Mussulman panee!—Chai, chai, chai-ee!

Tahsa chai, garrum, garrum!—Paan! Paan! Paan!”

There, now, you may take your hands away

from your ears! The first two were cries of the water sellers: “panee” is “water”—yes, Matt! “Nimboo panee” is therefore “lemon

water”—lemonade, exactly! Very good! There is water for Hindoos, Hindoo panee, or water for Muslims, Mussulman panee. The next, chai—very grating, yes, Antoinette—is a

tea-seller’s cry: “Fresh tea, very hot.” Now, you will find this a curious

touch: one purchases the tea in little handleless cups made of unglazed

pottery, drinks the tea and then throws the cup away! Partly for hygiene,

Antoinette, yes, and partly because the Indians would not wish to drink from a

cup that had been used by a person of a different caste or religion. What is caste? Similar to a social class,

dear, there are high and low castes, but perhaps that is for another day. Yes,

Tessa, darling, the Indian languages are very strange!

The final cry was not “water” again, Matt,

but “paan”—there is no translation. A

mixture of some spices and flavourings with an Indian nut which has certain

drug-like qualities: certainly a calmative. Children are not permitted it, and

English people do not usually partake. The mixture is rolled up in a special

leaf, like a little green packet, and popped into the mouth whole, for chewing

slowly. And the amazing thing is, that the leaf positively melts in the mouth!

…Er, yes, Matt, that certainly proves that someone

has eaten paan, but let us leave it

at that!

We did not pause for long on the quayside,

for the officials at the Lucas & Pointer offices had sent a carriage down

in the expectation of the ship’s arrival—that is quite correct, Matt, they

could not know exactly, and so the carriage had come every day for the last

week—and we set off for dear Ma Maison with only a little argument as to whether the window should be up or down! For

the Indian sounds and smells were not welcome to all of our party.

It is almost

eleven o’clock, Gil baba—hush,

Matt—and so we shall have our chota

huzzree—yes, milk with bread and butter, Tessa—and soon Ponsonby sahib will be down! No Indian biscuits

or cakes today, dear ones, for Matt’s Mamma has written to remind us that too

much sugar—No, nor the spicy sev

“worms”, children, you are not to have too much hot and spicy stuff: now, hush!

Sometimes when one is very far away from England one longs for a simple slice

of good white bread and butter with a glass of fresh milk! –No, Antoinette,

dearest, had you not gathered? Indian cuisine has no notion of soft, leavened

bread as we know it: they make flat, er, one has to call them breads, there is

no other word in English, but they more nearly resemble pancakes: flat

pancake-like circles of dough about six inches across, which are eaten while

they are still warm. Chupattees,

dear, of wholemeal flour, but there are also dosahs, from the south, more like heavy pancakes, and poorees, which are fried up in butter or

oil. They do not in general use yeast, but there is a bread called naan, much puffier than the flat pancake

ones, generally made in a big leaf shape, and very tasty—

Goodness, here he is! Down already! How are

you feeling today, Ponsonby sahib?

Very well? That is excellent news. –Children, do not all shout at once! Come

and sit down here, dearest sir. Yes, we are still telling them the story—at

least, we have got as far as India and Antoinette was asking about the breads. Only as far as India, yes, dear Ponsonby

sahib! Oh, dear! There have been

several digressions, you see. –Show him what you have writ about the breads,

dearest girl, and he will help you with the spelling. And perhaps explain more

clearly how the Indian breads are made, for he can cook better than any woman!

–It is true, Matt. Dearest, we told you of that: he had to learn when he was

being a spy!

Ponsonby Sahib’s

Receet for Chupattees

Take a good scoop of wholewheat flour,

mix with a little water & salt to form a stiff dough. Knead well. Set in a

bowl with a damp cloth to cover but not touch & leave while you prepare

other dishes. Break the dough into lumps, in size between that of a walnut and

a billiard ball, and roll in the hands until smoothly spherical. Then flatten

into a circle. Cook on a hot iron plate on one side until bubbles begin to

form, flip over, cook until the dough puffs up like a bullfrog. Make a little

pile of them, keeping warm in a cloth, with a little ghee between them, until half a dozen are ready. They must not get

cold, as they will then be very tough. They are good with bujeas* or hot, spicy curries.

* A

bhujia (bujea is the 19th-century spelling) is a simple fried, spicy

vegetable dish, usually with onion in it. It is cooked with very little water.

We would probably class it as a vegetable curry. –Cassie Babbage

Oops, possibly that last point should not

have been mentioned, Ponsonby sahib,

as little stomachs have just been told that spicy food is not good for them! –We

have had letters from their mammas, dear sir. No, well, it is the custom to

visit one’s friends and relations up and down the country at this time of year.

Besides, in these days of the wonderful trains, it may result in a brace or two

of grouse! –Let Ponsonby sahib assist

you with that glass, Gil baba. Not a

baby—no. Then hold it carefully, dear.

Now, as our

hero is downstairs and feeling very well, perhaps he might help us to tell

what happened on our return to Ma Maison! We have already told them of the busy

streets—and the snake charmers, yes, Matt! Oh, yes: Matt wishes to ask you

about the precise construction of a punkah,

dear sir. –Give him the sketch, dearest boy, and he will correct it for you.

There! Levers, is it? Fancy an old fan

being so scientific! Ponsonby sahib,

they will not understand if you tell them of the wonderful ancient observatory

in Delhi, for only Matt has been taken to see Greenwich, and he will naturally

expect it to be just like it. Yes, if you draw it for him, of course he will

understand! Very well, then, Matt, but later. It is much, much too scientific

for the little ones. Er, well, we have told them of Dr Little and of Indira,

dear sir, so— Well, it is their family history, after all, and the little ones

were not present for all of it.

No, children, you did not miss any of the

exciting bits, and we have not yet had the elephants, Tessa. Now, the next part

is not very exciting for little ones, so you may run and play—Stay with

Ponsonby sahib? Very well, dear ones.

A Conference with Dr Little,

as Told by Ponsonby Sahib

We were sitting in the library at Ma

Maison. Dr Little leaned back in a capacious armchair, very much at his ease,

and blew a smoke ring. “So y’spent the entire summer being toad-eaten at

Tamasha by as nice a selection of apkee-wastees

as ever walked—well, I ask you? Forbes memsahib?—and

went on to Maunsleigh to discover that Jarvis Wynton’s wife is a sensible woman

what didn’t dredge up anything that even looked like bein’ about to offer for any

one of ’em.” He blew another smoke-ring. “Excellent cigarillo, Gil. One of old

Henry’s, is it?”

This was typical Little, out of course. “I

would assume so, since it came out of that box that you disinterred from his

study,” I replied unpleasantly.

“It ain’t a box, dear fellow!” he said, shocked. “Humidor. Spanish work, I

think.”

“Have it,” I returned.

“Very funny.”

Sighing, I explained: “No, I mean it. I

prefer a hubble-bubble pipe, myself, though you need not noise that around

Calcutta,” —Little merely eyed me drily—“and the things are wasted on me. Have

the box—beg pardon, humidor—and whatever may be left in it.”

The doctor’s eye brightened. “No, well, if

you’re sure, Gil?”

I was very sure, and the doctor offered

fervent thanks, then urging me kindly to go on. But as I pointed out, he knew

the most of it—even the bits I didn’t

get round to writing him before we left!

He smiled slightly. “Self-evident, dear

man. Well, Miss Lucas is incapable of giving in to her feelings, isn’t she? I

grant you the business with the local medico was all highly commendable;

nevertheless she is, if you’ll stop to reflect on it, the sort of woman that

makes a specialty of a life of martyrdom in spite of all the delights that a

bounteous if misguided Nature can spread in her path. Then, Miss Tonie, having

never managed to work up much faith in the innate goodness of man, or rather of

the male half of humanity, in the first place, has discovered in the second

place the feet of clay of one particular individual, and is on course to

despise the rest of our sex for as long as she draws breath. The which, unless someone takes very good care, will not

stop her from marrying some unfortunate fellow and rendering the rest of his

existence a misery.”

“Myself being the someone, do I conclude?”

“Oh, only if y’volunteer for the duty,

Gil,” he said drily. “What about this Welling chap Miss Josie keeps going on

about?”

“I doubt she cares the snap of her fingers

for him. He is an amiable fool, who would doubtless do his best to make her

happy. She, however, would not for an instant pause to endeavour to make him

happy. His mother is said to rule his life, and it is a rôle into which Josie

would very easily step.”

“Hm. Many marriages end up that way, Gil.

Not saying it’s ideal, by any means, but if the gal wants him, would it be so

bad?”

I hesitated. Very likely Little would not

care to hear that in my opinion such a marriage as that would be abominable,

and not a fate, I was very sure, which Henry Lucas would have wished for any of

his daughters. So I merely said: “Probably not.”

Dr Little did not press the point, merely

grunted, and introduced the far less controversial topic of horseflesh, Colonel

Langford having written to report that Lord Sleyven had journeyed all the way

to Ireland to remedy the deficiencies of his late cousin’s stables.

The topic having eventually been exhausted,

the doctor asked on a cautious note: “Tell me, old man: did young Charlie

Hatton come out with you because he’s got an eye on a slice of old Henry’s

fortune, as rumour has already told me, or because he’s reconsidering that idea

of managing a tea plantation?”

“The excuse he offered me was that his next sister is due for a come-out next Season, and

he intends to escort her and his mother home. Possibly I looked as if I didn’t

believe a word of it, because he then added the additional excuse that his

father is still keen on the tea idea.”

“Given that Mrs Hatton has travelled home

by herself or with only a daughter or some other mem for company untold times— And back again.” Dr Little shrugged.

“Quite.”

“You cannot let it go at quite, dear man!

Did romance flower aboard ship?”

“You mean rumour hasn’t yet apprised you of

that one? No, well, in actual fact his tactics were exceeding cunning,” I

admitted grimly, “and I came to the conclusion not only that there is

considerably more to that young man than meets the eye, but that with a few

more years to his credit, he could turn into a very nasty piece of work

indeed.”

“Oh?” responded the doctor mildly.

“You don’t seem surprised.”

“Don’t know that I am. I’m the one that

tended to his childish aches and ailments, y’know. Real or feigned. No, well,

Mrs Hatton ain’t the sort to be taken in by a few moans and complaints of a

belly-ache that mysteriously clears up an hour before the regiment’s due to

parade on the maidan—though I ain’t

saying he didn’t try that on, too. No, but the time I’m thinking of… It was

just before they sent him home to school. The brats was all attending Mrs

Abbott’s dame school. Dare say y’might not remember her: hard-faced female with

a moustache that’d do credit to a hardened subadar

of twenty years’ standing, and the shoulders to match. So Master Charlie comes

down with a fever, a trifle odd, y’know, for there was nothing much goin’

round. Gave him a good going over: he was hot enough, tongue a nasty

colour—well, could have been anything. But his Ma said he hadn’t been casting

up his accounts, so that was a bit odd. Brats get a bit of a fever, they

usually do. No sign of the runs, neither. But in this climate discretion’s the

better part of valour, as y’know, so I prescribed a draught and a couple of

days in bed. I called in next day and he seemed a lot cooler, but complained of

pains in the joints. Well—could have just been growing pains, but I told his Ma

to keep an eye on him and to send for me immediate if the fever came back. But

it didn’t, and next time I popped in he was sitting up in bed happy as Larry

eating a curry and Mrs Hatton was only waiting for me to agree he could go back

to school to send him off.”

“So back he went, having missed what? A

spelling test? Mathematics?”

“Just wait,” warned the doctor. “I went

back a week later: poor little Bessy—y’won’t remember her, Gil, dare say: poor

little thing was took off in the cholera epidemic the following year—frail

little thing with a great mass of yaller curls—well, she was down with a fever,

and yours truly says to her it’ll only be the thing what Charlie had, you’ll be

as right as rain in a day or two. To which Bessy replies it can’t be, because

she wasn’t naughty like Charlie, and bursts into tears. And we get it out of

her that she thinks Charlie was sick as a punishment for having made a dummy

out of a dress of Ma Abbott’s what he pinched from the dhobi-wallah—or so the story ran, dare say he bribed or blackmailed

the fellow—and stuck it up in front of the classroom and tra-la-la. –Little

Bessy’s conclusion that he’d got sick as a punishment being the direct result

of regular attendance at the Reverend Gilliatt’s establishment,” he added on a

sour note. “Mrs Hatton wasn’t too pleased, as you can imagine, and got it out

of the poor brat that Master Charlie had missed the day when the whole school

was punished for it. Ma Abbott had held an assembly and threatened ’em all with

punishment if the culprit hadn’t owned up by the next day, y’see. Five hundred

lines to be written out after school for the lot of ’em, plus six strokes each

for the boys and a hundred lines more each for the gals.”

“I get your drift perfectly.”

“Aye. Well, one can understand any lad

doin’ the thing in the first instance, ’specially given Ma Abbott. Then dare

say a fellow might well lose his bottle at the thought of owning up to it. But

to go so far as to get out of the punishment that the whole school was being

favoured with on his account—” The doctor shook his head.

—Yes, children, Charlie was a very naughty

boy. Yes, of course he would have been punished when his mamma found out what

he’d done. Hush, now, if you wish to stay. Let Ponsonby sahib go on with the story.

“So, what did happen on board?” asked the

doctor.

I hesitated. “It’s actually dashed hard to

describe… I expected he’d try to charm Tiddy, but he didn’t. He was just very… Well,

behaved like they were two pals from the chummery,

but still managing to make it clear that he was aware she was a girl.”

“Uh—only a girl?” asked the doctor

cautiously.

“No, Tiddy would be the last one to stand

for that, as you know. No, dashed if I know how he… Well, there was one day she

was wearing a frilly thing and he laughed and congratulated her on her

appearance, adding that she looked quite like a girl. No, well, don't look at me, but if I was to say he had the exact

same expression on his face as d— Hatton used to when he was flattering Mrs

General Hayworth with some far-fetched compliment that a purblind child of two

wouldn’t have been taken in by?”

The doctor raised his eyebrows, whilst

simultaneously pulling down the corners of his mouth lugubriously.

“Aye,” I agreed to this grimace: “tacitly

recognising the both of them knew it was nonsense? Something like that.

Standard tactic of the ladies’ man, I dare say.”

“Mm. That as far as he went, though?”

“No: Charlie Hatton’s a fellow what hedges

his bets, and in the case the cosy note of old comradeship with Tiddy shouldn’t

develop into anything warmer, there’s always Josie.”

“He ain’t a title, though.”

“Apparently he don’t need to be, Little! She offered him considerable

encouragement. The thing is, Master Charlie is much too fly to fall over

himself at the mere batting of an eyelash. He let her become quite piqued at

not being able to add him to her list of conquests, whilst at the same time

offering her just sufficient encouragement to—ah—whet the edge of appetite,” I

ended on a distasteful note.

“Tactics worthy of a fellow of twice his

years and thirty times his experience, in short. And what did Tiddy think of

this appetite-whetting?”

“You don’t think he was gaby enough to do

any of it in front of her, do you?”

Dr Little raised his eyebrows and pursed

his lips in a soundless whistle.

I sighed, got up, fetched the humidor and

handed it to him silently.

“Er—take it and go, do I, Gil?”

“No,” I replied heavily. “Just light up

another. It may stop you making those faces.”

Grinning, Dr Little lit up another

cigarillo, leaned back in the capacious armchair of the library at Ma Maison,

and blew a smoke ring.

|

| "Four humidors from the Maunsleigh smoking room" Photographs by Jack Cooper. Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

—Yes, Charlie Hatton was a nasty fellow,

Tessa, but if you are bored, you may run along. Elephants, Ponsonby sahib? But was not the invitation to the

hills next? But of course, dear sir, the elephants may be worked in! –Why, here

are Madeleine and Mr Thomas! Come along and sit down—no, no, it is not

inconvenient, for Ponsonby sahib was

just about to help us tell of our trip to the hills after we had gone home to

Calcutta. –Yes, he showed Matt how a punkah

works, but you may show the diagram to Mr Thomas later, dear boy. Now!

A Trip to the Hills

A very flattering invitation had just been

issued to Miss Angèle Lucas. The weather in Calcutta was now very hot—though

not near as hot as it had been in June of ’16, when the maidan cracked—and fashionable Anglo-Indian society was leaving in

droves for the hill stations.—The maidan

is the big parade ground, children.

Ponsonby sahib looked limply at Mademoiselle. “I cannot imagine why Mrs

Allardyce should have singled Tiddy out—but I do see that it would be unwise to

refuse, Mlle Dupont.”

“Indeed,” agreed Mademoiselle primly. The

widowed Mrs Allardyce gave the most sought-after parties in Calcutta, was persona grata—nay, gratissima—at Government House, and, in short, was the most

sought-after lady in Calcutta. She was—well, Ponsonby sahib would not have been so bold as to hazard a guess at a lady’s

age. But certainly she had a daughter of around Tiddy’s age. Miss Allardyce,

having been sent back to England for her schooling, had been on the boat coming

out and had made a friend of Tiddy. Attaching herself to her, as a weaker

nature often will to a stronger one. They did not appear to have anything in

common outside their gender and their age, but Tiddy had treated Miss Allardyce

kindly and had not seemed averse to her company—in marked contrast to Josie.

She was now reaping the reward of this forbearance—poor Tiddy!

Trying not to laugh, Ponsonby said to Mlle

Dupont: “It is just Tiddy and yourself, is it?”

“Oh, quite. Mrs Allardyce did not extend

the invitation to Josie.”

“No. Well, serve her right for behaving

like a little cat to poor Miss A. on the boat. Very well, Mlle Dupont: you and

Tiddy should accept Mrs Allardyce’s invitation. Er—as you know, I had planned

to get up to the hills in any case this summer, to inspect Mr Lucas’s tea

plantation. Should I perhaps take the other girls to Darjeeling instead of the

plantation?”

“Indeed not, monsieur. I perfectly understand that Josie will be vairy

disappointed, but she might find herself excluded from certain of the choicest

entertainments if you were to attempt Darjeeling this year.”

“Mm. Well, the tea plantation it shall be.

And we can stop off in Patapore on our way. I don’t know whether you know of

it, Mademoiselle: it is about a thousand feet up in the hills. About three

days’ journey by elephant from the city. Quite a popular spot in the hot

weather, though not as fashionable as some. Dr Little has a pleasant bungalow

there.”

“That sounds delightful, monsieur,” she said politely. Ponsonby’s

eyes twinkled but he did not laugh, merely advised her to break the news to

Tiddy, at which she bobbed very properly and went out looking entirely prim.

Ponsonby sahib leant back in his chair and laughed. Quite apart from the

fact that she was keeping the girls in order and had very much improved the

appearances of both Tiddy and Josie, Mademoiselle was a continual source of

entertainment in herself!

In Folkestone Marie-Louise Dupont moved in

very refined circles indeed. The slight, so-charming French accent covered a

multitude of, if not sins, certainly lacunae; and the genteel dowagers, the

retired majors-general, the officers’ widows and so forth who lived in the

pretty houses on the outskirts of the town had all accepted her

unquestioningly. An émigrée, you

know: the family lost everything in the shocking Terror. So sad. In actual

fact, M. Dupont, still very much alive in spite of the rumour to the contrary

which his daughter had allowed to be credited, was a prosperous retired

butcher. Mademoiselle had accepted Ponsonby’s invitation to accompany the Lucas

girls to India as their chaperone most readily and graciously. Exactly how she

had managed to intimate she would prefer to be known there as merely Josie’s

and Tiddy’s late Maman’s old friend rather than a former governess was not

clear to Ponsonby sahib, when he

looked back on it. Nevertheless he was quite clear that it was so. Mlle

Dupont’s own maid had accompanied her on the voyage and well before the ship

docked at Calcutta it was very plain to everyone—indeed, one glance at Tiddy’s

hair was sufficient—that Jeanne’s rôle was to carry out Mademoiselle’s decrees.

—No, well, to us older ones it is funny,

Matt. Mademoiselle sounds like a dragon? Oh, dear! She was strict, dear boy, but not too strict; and very well-meaning.

And truly cared for us all. The elephants are coming, Tessa. Yes, straight

away!

It was not positively necessary to journey

to Patapore by elephant, but once one got into the hillier country it was an

easier way to proceed than by carriage, over the rough Indian roads. So the

offices of Lucas & Pointer were advised that three of the elephants and

their mahouts would be required, and

the party for Patapore set off with the young ladies and Sushila Ayah in a carriage for the first part of

the journey but Ponsonby sahib riding

in state high on his elephant, like a maharajah!

The servants at Ma Maison, thrilled to have him home again, had not spared

every effort, and the elephants that arrived from their stable looking merely

clean and neat, newly hosed down by their loving mahouts—not to say with the help of their own hoses!—reappeared on

the sweep when the party was ready bedecked with great strings of flowers,

their huge ankles strung with rows of tiny bells, larger bells depending from

the tusks, and their foreheads and trunks beautifully painted with designs of

red, blue and yellow. We could not but admire the effect, though some of us

were trying not to laugh, too. Into the bargain the largest elephant, intended

as Ponsonby sahib’s own ride, had a howdah which would scarce have been out

of place in the Governor-General’s train!

The Viceroy, you would say nowadays, the burra-sahib who represents the Queen,

children. Look: Tonie has sketched a howdah:

a little shelter, sometimes like a tent, sometimes a more permanent structure,

which goes on the elephant’s back, high, high above the ground! How does one

get on? A very logical question, Matt. You wish to know where their hoses are,

Tessa? Their trunks are their hoses, dearest!

Yes, give Ponsonby sahib the pencil, Antoinette. Look, the elephant is sucking the

water up with his trunk and now… Whoosh! He’s squirting it out all over his

back! No, an elephant would not do that while you were sitting on him—or her,

many of them are females—for they are very well behaved, not unlike a well trained

horse. Of course the picture is for you to keep, Tessa, dear! –Yes, Ponsonby sahib will draw an elephant especially

for Gil baba. –Two elephants, one kneeling down so that his passengers may climb

on! And that is how one gets on,

Matt! –Say thank you, Gil, dear. Not you, Ponsonby sahib, the other Gil! Oh, dear! Now we are all getting silly!

They understand commands, Mr Thomas, just

as a well trained dog does: they are highly intelligent creatures. The mahout give the command to kneel, you

see, if necessary backing it up with a tap of his crop. Of course if the

elephant knows you well he will sometimes lift you onto his back himself—even

without being prompted, for they usually lift their mahouts—and that can be quite a surprise! He looks round at you

with his big gentle eye, Tessa, and then curls his great big trunk round your

waist—very gently—and then lo! You are up in the air before you know it! No,

not in the howdah, dear, but when his

back is bare or there is just a big double seat upon it: two sides to it and

one sits facing sideways, in that case. An elephant is very strong, dear: he

could carry twelve people with ease. –Not only as beasts of burden, Mr Thomas:

in the forested parts they are used to haul great felled tree trunks. Yes, you

could call it jungle, Matt, indeed!

That’s right, children: run and play at

jungles and elephants. The next part of our story is about older people’s

concerns. No, no more elephants, Tessa. Yes, Gil baba shall have an elephant to himself! Off you go! –There is time

to tell you a little of the hill station and Tiddy’s experiences there before

the midday meal, but we have to admit, Mr Thomas, that you may not find it

exciting. Stop laughing, Ponsonby sahib: it

was not so funny as all that! Now you cannot wait, Mr Thomas? Very well, but

pray do not say you were not warned!

Tiddy Experiences a Hill

Station

(Largely in Great-Aunt Tiddy’s own words)

|

| "A charming scene near the hill station" Photograph, circa 1865. Courtesy of Miss Thomas |

It was a typical Darjeeling day. Tiddy, as

usual, woke early to find Mademoiselle’s Jeanne already in attendance,

proffering morning chocolate. The beverage was not entirely unexpected;

nevertheless she groaned: “Du chocolat?

Aux Indes?”

Ignoring the tone, Jeanne returned coolly: “En effet, Mlle Angèle.” And went on to

remind her that it was the done thing for young ladies. And as soon as Mlle

Angèle had had her bath, she, Jeanne, would attend to her hair. By now Tiddy

knew it would be pointless to argue. The only possible tactic was to avoid

discussion and get the thing over with. At very long last the result was

revealed. A knot of ringlets falling from a braided circlet. And side-curls:

worn rather high, they succeeded in mitigating the roundness of Tiddy’s

youthful features.

“I look older,” she conceded. “I shall

never be able to do it for myself, you know. And nor will Nandinee Ayah.”

Replying with dignity that Mlle Angèle

should not be expected to do her own hair, and noting by the by that one would

not expect that Black woman to be able to do any such thing, Jeanne made a

dignified exit. Glumly Tiddy went downstairs to show the result of the

morning’s labour to Mlle Dupont.

Mademoiselle was discovered in the front

parlour of Mrs Allardyce’s charming verandahed house. She was wearing what most

certainly must fall within the definition of a morning dress: since it was

morning, and since Mademoiselle had a very strong sense of the fitness of

things. But it was, noted Tiddy with a certain grim resignation, about five

thousand times smarter than anything ever seen at home in the Tamasha morning

room. Even on Josie’s back. You could have described it as narrow grey and

white stripes. Intimidating grey and

white stripes might have put it better. The dress was not over-smart, but dowdy

it was not. The stripes had been used vertically in the high-waisted skirt and

the long sleeves, and diagonally in the bodice, almost with a sort of tucker

effect, though as tuckers were now, according to Josie, “extremely outmoded for

all but little girls,” one would not have dared to voice the thought. The

not-tucker was decorated with some tiny buttons, and above that the neckline

was filled in with the same stripes used horizontally, and above that again the

neck itself was encircled with more horizontal stripes, finished off with a

tiny frill of lace. Which lesser persons might have repeated on the cuffs, but

which Mlle Dupont had not. There was no flounce: merely, a hand’s-span above the

hem, a tiny bias strip of the stuff, the stripes used diagonally.

Intimidating—yes.

|

| "A morning dress" Mezzotint, hand-coloured, late 1820s (from a portfolio of mounted sketches & prints, Maunsleigh Library) Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

“Much better!” she said briskly in her

native language.

“Sans

doute, Mademoiselle,” agreed Tiddy glumly.

No-one else was yet down. “Tiddy, my dear, since

we are alone, I feel I must say this. One understands your reluctance to go off

up the country,” said Mademoiselle as to the manner born, “on a visit to some people

whom you barely remember from old India days in the company of one unhappy

sister, one grim sister and one sulking sister. Nevertheless the question

remains: why did you agree to come to Darjeeling instead?”

Tiddy scowled. “To get it over with: I have

to become a young lady, so it may as well be now. At least I may do it here

without Josie laughing over the thing.”

“Of course. And Colonel Ponsonby? What do you

intend there?” she said baldly.

Tiddy glared. “Mademoiselle, the others

don’t want him!”

“That is certainly true,” she agreed

calmly. “But do you?”

Tiddy stuck her pointed chin out. “Wouldn’t

it be sensible? Someone has to keep Papa’s fortune in the family!” Mademoiselle

merely looked bland. Smiling uneasily, Tiddy admitted: “I don’t think I would dislike being married to him.”

Mademoiselle looked thoughtfully at the

smile and wondered what, exactly, it was concealing. “Non? Dis-moi, mon ange, how did you think of him when you were

little? Nothing to compare to your feelings for pretty Charlie Hatton or the

so-lovely Mr Feathers?”

Again Tiddy produced that uneasy smile.

“Well, he isn’t good-looking… I liked

him better than anybody else I knew. Colonel Wynton was our colonel, of course,

but in a way I suppose I thought of Ponsonby sahib more as my colonel than anything.”

Mlle Dupont nodded slowly. Certainly the

late Mrs Lucas had mentioned her husband’s concern that Tiddy had seen herself

as Ponsonby’s trusty aide: that would fit, yes. But all that uneasiness? There

was something there that Tiddy was not telling her. Was it just resentment that

the disposition of their fortunes, not to say an entire third of their father’s

estate, was in his hands? But Tiddy had never been at pains to conceal that

from her.

“Not that it can signify, Mademoiselle,”

she said firmly, “for I have made up my mind that it must be me. If I don’t do

it, Tess will be bound to sacrifice herself. And even if she has decided

against Dr Goodenough, I don’t think she would be happy. She likes Ponsonby sahib but she doesn’t love him. She is

not the sort of woman who could be happy in that sort of marriage.”

“En

effet.” Privately Mademoiselle decided that, if it should turn out that

Tiddy could not in the end like Ponsonby enough, there should be no question of

her tying herself up to him: a man more than twice her age? No. But if she

could, why not? A girl of Tiddy’s station in life must marry. And, though of course

men knew nothing—mais rien du tout!—of

how women might react to other men, still the fact that their father had seen

fit to tie the fortune up in this odd way certainly seemed to speak very, very

well of Colonel Ponsonby.

“Papa liked him very much, you know,” said

Tiddy suddenly.

Mademoiselle jumped a little. “Yes. That

must count very greatly in his favour, ma

petite. Et maintenant,” she said gaily, “voici

Mlle Allardyce! Good morning, my dear Miss Allardyce. What do you say we drive

out as soon as we have breakfasted?”

“What about Mrs Allardyce?” said Tiddy

limply.

But Violet Allardyce explained that her

Mamma was taking her breakfast in bed and did not usually drive out so early.—Tiddy

at this point avoided Mademoiselle’s eye: she already knew that energetic

person’s opinion of fine ladies who did not rouse themselves to see to their

households of a morning.—A drive would be delightful. And so many of their

friends from Calcutta were now up here: they were sure to meet someone whom they

knew!

Sure enough: scarce had the delights of the

little hill station with its great drooping deodars and their pools of icy

shade, its balconied wooden shops and its multiplicity of verandahed bungalows

been sampled, than it was:

“Ah! There is dear Major-General Harkness!

But naturellement I recall him,

Tiddy, he was at Mrs Colonel Peckham’s delightful card party in Calcutta. You

may oblige me by being vairy polite, mon

ange, and acting as if you wished to see him this morning, and remembering

his stiff leg, for after all he knew your Papa, non? –The left. And if he wishes to kiss your hand,” added Mlle

Dupont, the shrewd little brown eyes twinkling but her face quite calm, “just

bear in mind that a lady does not shrink and say ‘Ugh, yuck.’”

|

| "Ready for the ball - Maj.-Gen. Harkness" Sketch, pen, ink & wash, watercolour, from John Widdop's journal, circa 1829. From the Widdop family papers |

“But Mademoiselle!” she hissed in agony.

“He gives—”

“Sss!

Tais-toi, ma chère. Major-General Harkness!” she cried as the barouche drew

up beside the stout elderly figure. “But what a delightful surprise!”

“–sloppy kisses,” muttered Tiddy, sotto voce, subsiding definitively. Ugh,

yuck.

Major-General Harkness, however, was soon

to pale into positive insignificance in comparison with Darjeeling’s other

figures of note.

“Delighted!” beamed General Porton, bowing

very low over Tiddy’s hand. –Enfeebled hand. The General was a fixture in

Darjeeling—though occasionally descending to the plains in the cooler months.

He was very fat, and old enough, at a wild guess, to be Tiddy’s grandfather’s

grandfather, and very scented, and tremendously—nay, horrifyingly—elegant. Yellow pantaloons and gleaming Hessian boots

that would not have disgraced Beau Brummel in his prime—were it not for the

figure inside ’em, naturally—with a blue coat of surpassing tightness, and a

lilac watered-silk waistcoat that almost outshone the splendour of the immense

neckcloth swathing his fifteen or so chins. At least the kiss he dropped on the

aforesaid enfeebled hand was not sloppy.

|

| "Old Porton in his d-- blue coat" Sketch, pen & ink, watercolour, from John Widdop;s journal, circa 1829. From the Widdop family papers |

The

creak from the corset as he bent would have been enough, Tiddy dared swear, to

overset the gravity of any maiden who not already been exposed this week to the

frolicking side-whiskers and totally bald pink pate of Colonel Brinsley-Pugh

(Rtd.), the fluffy red curls of Major Narrowmine, retired from a distinguished

career quite some time before Waterloo, so how the curls had remained that red

must remain a discreet mystery, and the terrifyingly martial boots, breeches,

tight-buttoned coat and salute—yes, military salute, though neither he nor Miss

Angèle Lucas had been in uniform at the time—of Major-General Widdop: like

General Porton, a fixture in the hill station. –Later discovered by

Mademoiselle to have spent most of his career back in England with responsibilities

in military provisions—well, someone had to do it, my dear. The retirement to

India being explained by his having come out to visit with his brother, a

Collector, that is, a District Officer of the East India Company, and having

simply stayed on. What Mr Widdop thought of his brother’s permanent occupancy

of his Darjeeling bungalow was not known for sure, though several theories were

current. Nor was the current ownership of the house exactly clear, and

speculation was rife upon this vexed question.

The gruffly military Major-General Widdop

affected to despise Colonel Brinsley-Pugh and Major Narrowmine, and had, his

expression, no truck with them. The bald-pated Colonel and the red-haired Major

were both frightfully well connected, and their main interests were two: horse

racing and a succession of name-dropping stakes. The former must depend on the

weather and the season, but the latter were run almost continuously: just as

you were thinking that Brinsley-Pugh had carried off the gold cup and

Narrowmine must now be retired honourably to grass, the latter would sprint

forward with a renewed burst of speed, and all bets would be on again. Of

course they cordially loathed each other—though, strangely, they were almost

inseparable companions.

|

| 'The Dandies - Brinsley-Pugh & Narrowmine after a tiff" Sketch, pencil & watercolour, from John Widdop's journal, circa 1929. From the Widdop family papers |

They both professed extreme delight at

meeting a Miss Lucas “at last”, paid Tiddy elaborate compliments, and then

endeavoured to get out of her just what her father’s estate was worth, and how

much she, Tiddy, might expect as her portion. Colonel Brinsley-Pugh assuring

her into the bargain that he remembered her delightful Mamma very well—very

well indeed! Tiddy did not even bother to ask if he meant her stepmother or her

real mother. For one thing, she was sure that either claim would be equally

fictitious, and for another, why prolong the agony?

—Exactly! Oh, dear! Of course it did not

get better—one could not expect it to. No, Mr Thomas, Tiddy did not precisely

become inured, either—oh, gracious,

now you have set Ponsonby sahib off

again! …Tell them about the tea parties and the sakht burra mems thereat, Ponsonby sahib? Very well, dear sir, but only if you promise—absolutely

promise—there shall be no invidious comparisons!

The majestic Mrs Martinmass poured tea.

Under Mademoiselle’s fixed stare, Tiddy remembered to praise it. Mrs Martinmass

preened herself, and offered small sandwiches and sponge cake. She then

endeavoured to get out of Tiddy just what her father’s estate was worth, and

how much she, Tiddy, might expect as her portion, but by now Tiddy was used to

this and countered it politely. And agreed, without even the aid of

Mademoiselle’s fixed stare, that she would be delighted to walk out with Miss

Martinmass at any time.

The crushed Miss Martinmass, thirty if she

was a day, and with a small moustache to boot, smiled limply and expressed gratification.

Not requiring her majestic mother so much as to glance her way, let alone give

her a fixed stare. Help.

…“I grant you the family name. But if he

has so much as set foot at Blefford Park, I am sure it is more than I have ever

heard!” said the intensely ladylike Mrs Whassett with a superior little titter,

handing cake.

Tiddy smiled palely. That must take poor

Major Narrowmine off with his cloak over his face, then.

“What delicious cake, chère madame,” said Mademoiselle politely into the silence that had

fallen in Mrs Whassett’s charming salon.

Jumping, Tiddy agreed hastily that Mrs

Whassett’s very ordinary fruit-cake was delicious. Actually it could have done

with a dash of brandy to liven it up. …Come to think of it, the criticism could

well be applied to the polite society of Darjeeling in toto. Oh, help!

—Yes, of course it is just like English

society at home, Antoinette: that is partly our point! Curious indeed, Mr

Thomas, that in those exotic climes we English should have found it necessary

to transplant our customs and attitudes so exactly. Small wonder the Indians

consider us doolally! But indeed,

Ponsonby sahib: of course it is only

natural to hanker after the only way of life one has ever known and try to replicate

it. Regardless of its suitability to the climate—yes, indeed, dear sir! Oh,

dear! –He is like that, you see, Mr Thomas: incapable of not seeing both sides of every question!

Now, Tiddy baba has not yet told you of all the significant persons who

adorned the hill station. –Pray stop laughing, Ponsonby sahib! Significant in their own little world, dear sir!

Brigadier Polkinghorne (Rtd.) remembered

Miss Angèle very well and was delighted to see she was out at last! This latter of course did not refer to the fact that

Tiddy was walking in the fresh air past the most respectable little emporia of

Darjeeling with Violet Allardyce and the crushed Miss Martinmass, but to the

fact that she was doing so in the persona of a young lady. In a

Mademoiselle-approved walking-dress with a smart, much-beribboned straw hat.

The gown was a soft shade of grey with tiny white dots, and the ribbons on the hat

were also grey, with some sprigs of white flowers tucked cunningly into them.

The whole rendering Miss Martinmass self-professedly aux anges. Even though the flowers bore no resemblance to any

botanical species that had as yet come within Tiddy’s cognisance. Either in

India or in England. Well, presumably Miss Martinmass was no botanist.

|

| "The Latest Ladies' Hats" Pencil, watercolour, circa 1828, artist unknown (from a portfolio of mounted prints & sketches, Maunsleigh Library) Courtesy of the Maunsleigh Collection |

Fortunately Tiddy did remember Brigadier

Polkinghorne, and was able to respond appropriately. Actually it would have

been hard to forget a tall, gaunt, craggy-looking gentleman who featured a

charming tortoiseshell lorgnette. Not a quizzing glass, no: a lorgnette. The

which he had now raised in order to admire Tiddy’s appearance. And would Miss

Tiddy allow him to present his very old friend, Mr Sebastian Whyte?

Mr Whyte in appearance was the antithesis

of Brigadier Polkinghorne, for he was very, very short and very rotund, with a

smooth, shiny, pinkish, finished look

to him. And where the craggy Brigadier, apart from the lorgnette, was

positively severe as to his dress, Mr Whyte was extremely elegant indeed.

Hessians that rivalled General Porton’s. And lilac gloves. And a quizzing

glass. The whole finished off with a very small flower in the buttonhole of the

quite exquisitely cut blue town coat.

Miss Martinmass was evidently extremely flustered

at the encounter: she became very lively indeed, giggling at a mild jest of the

Brigadier’s and positively choking over a scarcely less mild sally of Mr

Sebastian Whyte’s. And confided to Tiddy, after the two had ascertained the

young ladies had it in mind to look in at Madame Lucille’s this morning and escorted

them thereto, that Brigadier Polkinghorne was an excessively attractive

gentleman: did she not find? So military in his bearing!

Very kindly Tiddy did not say that in her

opinion she had no hope, there. And was able truthfully to agree that the

Brigadier was very military. Only breaking out to the point of adding, but would

not his short sight have been a handicap in his military career?

…Major Narrowmine sniffed slightly. “True,

the name is Whassett. But, remark, my dear Miss Angèle, not Coulton-Whassett.”

This was self-evident; but clearly it had

some extra significance to the red-headed major. Tiddy smiled and nodded

gallantly. She was rewarded for this effort by then receiving chapter and verse

on the Coulton-Whassetts, the late

Lord Coulton-Whassett’s ending in the River Tick, the sale of the C.-W. town

house and picture collection to a rich nabob, the unfortunate marriage of a

Mirabelle of that ilk, the subsequent

marriage of the granddaughter of the same to… By the end of it she was so

groggy that she did not even ask: Which

rich nabob? But she was certainly able to conclude that it must take Mrs

Whassett off with her cloak very much

over her face. So much for feeling sorry for Major Narrowmine!

—Thank you, James, we shall all come

directly. Just assist Colonel Ponsonby, if you would. And pray tell Nurse that

since he is down the children may have their midday meal with us.

Indeed, there was more, Madeleine, dear,

considerably more, and after the meal perhaps you would like to look at some of

Tiddy’s baba’s old letters: Tess has

kept all our letters safely in a portfolio, which is in the study here.

Great-Aunt Tiddy’s letter to

her sister Josie,

written in Darjeeling [1829]

My Dear Josie,

I still

have no news, but as ordered, am writing. Life here is compound entirely of

mixed hypocrisies and social nothings. The which, avouons-le, frequently confuse themselves, to such an extent that

one cannot say if the example in question be one or the other. Or both. Mrs

Allardyce is all that is kind, I must hasten to add, and does not practise

hypocrisies on me. But the moment one sets one’s toe outside the door, it must

commence. To take but one example of the five hundred which occur every week,

we called recently on Miss MacDonnell. Do you remember her? Her brother was

Maj.-Gen. MacDonnell, and she always had little terrier dogs. (MacDonnell with

the accent on the last syllable, not the penultimate, tu t’en rappelles?) The

great-grandfather dog, old Tinker-Terrier, died last winter, is that not sad? I

remember him as such a frisky fellow! Mrs Freda Tinker-Terrier, his

granddaughter, is still with us, if a little stiff in the joints, and her

daughter, Mrs Dotty Tinker-Terrier, is a stout matron with entrancing white

spots on the black ears. And Mrs Dotty’s son, Master Tinker-Terrier the Second,

is as merry a young grig as one could possibly imagine! There was no-one else

present in her tiny bungalow with its great deodar tree, and we had an entirely

cosy visit. The main topic of conversation being the improbability of Mrs

Martinmass’ succeeding in forcing poor Miss Martinmass upon the military

Maj.-Gen. Widdop, it being in the highest degree unlikely that Miss M.’s charms

will have the power to induce him to forego the comfortable state of

widowerhood which he has enjoyed these fifteen years past. All this over Miss

MacDonnell’s delightful seedy biscuits which she bakes herself, not trusting

her Indian cook to do any such thing, and with which only the most welcome

guests are favoured. (Not Mrs

Whassett, Mrs Martinmass, and their ilk.)

Well and good: we make our farewells and

retire, as to myself, with a promise of being entrusted with Master

Tinker-Terrier as company on my walks whenever I desire; and are scarce two

doors down the street before it is: “Of course, she is a nobody, my dears! But

then, she knows everybody.” You may gather how untried in the furnace I as yet remain, for I foolishly reply: “But

Mrs Allardyce, I thought you liked her?”—A light laugh: “But I do, my dear:

what has that to say to anything?”

Well! But

it is all like that. We encounter craggy Brigadier Polkinghorne as we stroll

homewards, and greet him with complete charm (Mrs. A.), meek complaisance (Miss

A.), grovelling complaisance (Mademoiselle) and insufficient civility (self).—“Tiddy,

ma chère, those giggles were

inappropriate.”—“But Mademoiselle, that lorgnette of his is so very silly.”—Another

light laugh from Mrs A.: “Of course, Tiddy, my dear! There is no need, however,

to let it show.”

And as to

Mrs Whassett’s fruit-cake! I voice, only between ourselves, of course, my criticism:

to wit, insufficient fruit and, or my taste buds deceive me, no brandy. (Mrs A.

you understand, having praised it to High Heaven.) This time she does not

bother with the light laugh. “Oh, quite. She has not the excuse of straightened

means, neither.” With a shrug worthy of Mademoiselle herself at her most

Gallic. Help!

Into the

bargain she had accepted with unalloyed rapture the woman’s invitation to

dinner for the following Saturday. We went, and while we waited for the

gentlemen to rejoin us, Mademoiselle and I were favoured with a very telling

evaluation of the quality of the said dinner by a Mrs Turner. To my innocent

eyes (and taste buds) the meal had seemed very fine. But the chicken ragoût was

eked out. The word “goat” not even

having to be breathed. Mademoiselle, of course, did not even look a criticism:

merely said respect-fully that she was sure Mrs Turner must be correct, but to

her it had all seemed delicious. Her culinary standards are of course very

high, so I could not forbear to ask when we arrived home, Had she meant it? She

refrained from speech, merely gave me a Look!

Mrs

Allardyce’s contribution was to note, with smiling

lightness, that Mrs Whassett had not managed to balance her table—had I

noticed? Oddly enough neither Violet Allardyce nor I had noticed, no. For

myself, I was placed between Mr Sebastian Whyte, point de vice in an evening coat that would not have disgraced

Almack’s, with an huge but chaste

pearl in his neckcloth, all smiles and chat, on the one hand; and on the other,

the gruffly military and inarticulate Major-General Widdop. So how could I have

been in a fit state to notice anything? Though I did recall, under Mrs

Allardyce’s smile, that Miss Martinmass had been placed between Mademoiselle

and Mrs Turner. “Oh, quite, my dear.”—And she explained, still with that

smiling lightness, that the whole thing was a deliberate piece of spite by Mrs

Whassett against Mrs Martinmass, in view of her hopes for Miss M. in the

direction of Major-General W.! Oh, Lawks a-mussy me!

As to the

rest, it is all bonnets and bows. Not beaux, no: I am sorry to disappoint you,

Josie. Though Major-General Harkness, he of the sloppy hand-kisses, has

favoured me with a posy. Before you read far too much into this, he is a

widower, yes. But he is also very, very proud of his bungalow’s “English”

garden.

Oh, I beg

your pardon: I do have another lover, his name is Master Tinker-Terrier, and I

adore him even more than he adores me!

I do hereby

solemnly swear that neither Mademoiselle nor kind Mrs Allardyce have bought me

any gowns, ribbons, bonnets nor shawls, but only one pair of gloves (Mrs A.).

And do faithfully swear to report any such purchases veraciously and honestly

to Miss Joséphine Lucas or her appointed deputy, to the best of my poor powers

of description.

With inelegant but sincere big kisses and

hugs to all the family, I remain,

Your loving

Tiddy

Mrs Beeton’s White Soup, A Recipe from 1861 *

1/4 lb. of sweet almonds, 1/4 lb. of

cold veal or poultry, 1 thick slice of stale bread, 1 piece of fresh

lemon-peel, 1 blade of mace, pounded, 3/4 pint of cream, yolks of 2 hard-boiled

eggs, 2 quarts of good white stock

Mode: -Reduce the almonds with 1

spoonful of water to a paste in a mortar. Pound the meat with the bread, &

add. Beat all together. Add lemon-peel, very finely chopped, & mace. The

stock should be boiling. Pour it stock on the whole. Then simmer for 1 hour.

Rub the eggs in the cream, put in the soup, bring it to a boil, & serve immediately.

* This is from the

recipe in the MS, which was headed only “White Soup.” Research has revealed it

is Mrs Beeton’s recipe. She also gives the recipe for the white stock, from

which we can clearly see that the secret of a good white soup is an excellent

stock. –Cassie Babbage

~~~~~~~~

White Stock

(To be Used in the Preparation of White Soups)

INGREDIENTS.--4 lbs. of knuckle of veal,

any poultry trimmings, 4 slices of lean ham, 1 carrot, 2 onions, 1 head of

celery, 12 white peppercorns, 1 oz. of salt, 1 blade of mace, 1 oz. butter, 4

quarts of water.

Mode.--Cut up the veal, and put it

with the bones and trimmings of poultry, and the ham, into the stewpan, which

has been rubbed with the butter. Moisten with 1/2 a pint of water, and simmer

till the gravy begins to flow. Then add the 4 quarts of water and the remainder

of the ingredients; simmer for 5 hours. After skimming and straining it

carefully through a very fine hair sieve, it will be ready for use.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please add your comment! Or email the Tamasha Cookbook Team at infoteam@senet.com.au